No other city or town in Crete is as important as the city of Heraklion. The city of Heraklion possesses a heritage that spans across hundreds of years and manages to bridge the gap created by time in order to embrace the progress of the future. Heraklion stands at the outskirts of the palace of Knossos, which historians know to be the heart of the ancient Minoan civilisation, and it has known times of peace and times of war.

In 69 BC, the city came into the bosom of the Roman Empire through the conquests of Quintus Caecilius Metellus. The Byzantine Empire took possession of the city when Rome fell. In 1204, when the Byzantine Empire was no more, Heraklion became a city under Venetian rule. In 1669, after 21 years of siege, the Venetians relinquished Heraklion and the whole of Crete to Turkish rule under the Ottoman Empire. Under this rule Heraklion remained, until Crete won its independence in 1897 and became one with Greece in 1913.

The Modern Face of Heraklion Today, Heraklion is a city that embraces its long and colourful past but is nonetheless busy with building bridges into the future. With around 200,000 people living within its boundaries, Heraklion is a busy, bustling city. Within the city is the Heraklion International Airport, the second largest airport in Greece in terms of size and traffic. It is also a very important port of call in shipping and sea-based transportation. Though a short drive out of the city will take the traveller to the most famous tourist attraction in Crete – the palace of Knossos – Heraklion itself has many interesting sights that should not be missed. Among these places that should be visited in Heraklion is the Liondaria or Lions Square, officially known as the Plateia Eleftheriou Venizelou. If Heraklion is the heart of Crete, then Liondaria is the heart of Heraklion. This is where people meet for business or for pleasure. Here, one can sit at one of the cafes and be served light Cretan meals while watching people. Other sites that should not be missed when visiting Heraklion are Koules and the ancient Venetian city walls. Koules, also known as the Castello del Molo and the Rocca a Mare, is a fortress that has protected Heraklion since the 13th century. It overlooks the old Venetian harbour. As for the ancient Venetian city walls, they are certainly worth a look as these walls were the ones responsible for making the Turkish siege of Heraklion last for 21 years. This is also the place where the famous Cretan philosopher Nikos Kazantzakis has been laid to rest. The heart of Crete beats in Heraklion, and a holiday to Crete will not be complete without an exploration of this city.

Crete claimed by many Greeks to be the most authentic of the islands,is by

far the largest.It stretches 256km(159mile)east to west and is between

11 and 56km (7and 35milos) wide.A massive mountainous backbone dominates

,with peaks stretching skywards to over 2400 metres (7.874 ft).In the

north the mountainous slope more gently,producing fertile plains,while

in the south they plunge precipitously into the sea.Crete is called

Megalonissos -the Great island- is what the Cretans call their home.

Great can certainly be applied to the Minoan civilization ,the first in Europe and one with which Crete is inexorably entwined.

With two major airports,Crete cannot be classified as undiscovered,but through its size and scale it manages to contain the crowds and to please visitors with widely divergent tastes.While a car is essential for discovering the best of the island,car hire is,fortunately comparatively inexpensive.

Phaestos Minoan palace -south Heraklion prefecture:

Phaestos was the second most important palace city of Minoan Crete. Of all the Minoan sites, Phaestos (fes-tos) has the most awe-inspiring location, with all-embracing views of the Mesara Plain and Mt Ida. The layout of the palace is identical to Knossos, with rooms arranged around a central court.

In contrast to Knossos, Phaestos has yielded very few frescoes. It seems the palace walls were mostly covered with a layer of white gypsum; there has been no reconstruction. Like the other palatial period complexes, this one had an old palace that was destroyed at the end of the Middle Minoan period. Unlike the other sites, parts of this old palace have been excavated and its ruins are partially super-imposed upon the new palace.

The entrance to the new palace is by the 15m/49ft-wide Grand Staircase. The stairs lead to the west side of the Central Court. The best-preserved parts of the palace complex are the reception rooms and private apartments to the north of the Central Court; excavations continue here.

This section was entered by an imposing portal with half columns at either side, the lower parts of which are still in situ. Unlike the Minoan freestanding columns, these do not taper at the base. The celebrated Phaestos disc was found in a building to the north of the palace. The disc is in Iraklio’s Archaeological Museum.

Crete was known as Kriti or the city as Handakas in past.

The archaeological site of Knossos is sited 5 km southeast of the city of Iraklion.

There is evidence that this location was inhabited during the neolithic times (6000 B.C.) . On the ruins of the neolithic settlement was built the first Minoan palace (1900 B.C.) where the dynasty of ruled. This was destroyed in 1700 B.C and a new palace built in its place.

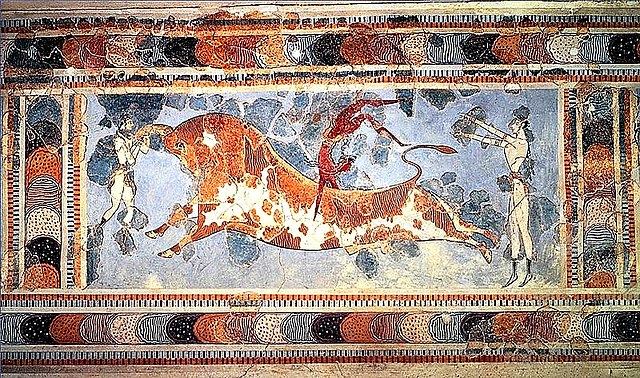

The palace covered an area of 21,000sq.m, it was multi- storeyed and had an intricate plan. Due to this fact the Palace is connected with thrilling legends, such as the myth of the Labyrinth with the Minotaur.

Between 1.700-1.450 BC, the Minoan civilisation was at its peak and Knossos was the most important city-state. During these years the city was destroyed twice by earthquakes (1.600 BC, 1.450 BC) and rebuilted.

The city of Knossos had 100.000 citizens and it continued to be an important city-state until the early Byzantine period.

Knossos gave birth to famous men like Hersifron and his son Metagenis, whose creation was the temple of Artemis in Efesos, the Artemisio, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world.

The site was discovered in 1878 by Minos Kalokairinos. The excavations in Knossos begun in 1.900 A.D. by the English archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans (1851- 1941) and his team, and they continued for 35 years.

The most important findings of the city of Knossos are:

The Great Palace”Prince of the Lillies”

The Great Palace covered an area of 20.000 sq. meters and had 1.400 rooms.

Every section of the Palace had a specific use. In the west side of the Palace were the chambers of the ceremonies, of the administration and of the public storehouse. The Throne room is also located here.

To the west of the Throne room was the great west Court of the Palace and the theatre, where all the ceremonies and gatherings took place. The East side of the Palace, had more floors, verandas and official rooms with wonderfull frescos, and was the side of the Palace where the Queen had her private chambers.

The entrance to the Palace today is through the West Court. The West Entrance leads to the Corridor of Procession. Its walls were decorated with a fresco depicting a procession, which today is exhibited in the Archaelogical Museum of Heraklion . To the left of the corridor is the Propylaeum of the Palace, where the huge double horns – a holly symbol of the Minoan religion- are located. A staircase leads to the Central Court , where the Throne room is sited, and another one to the upper floor. There are various rooms on the same level with the Throne, like the Antechamber, the Pillar crypt, the room of the Tall Jar and the Treasure room of the High priest, were various precious objects, now exchibited at the Iraklion museum, were found.

Near the south west corner of the Court a road leads to the Corridor of the Procession were the famous fresco of the “Prince of the Lillies” was found. The original is displayed in the Iraklion museum, and a copy located in its place..

The Little Palace.

It is located west of the Great Palace and is the second bigger building of Knossos. In one of its chambers was found the wonderfull Bull’s Head made of steatite, which is exhibited in the Archaeological Museum of Heraklion.

The Royal Villa.

It is located northeast of the Great Palace and it is considered part of it. A magnificent jar was found here, with papyrus in relief.

The House of the High Priest .

This building is considered to be the House of the High Priest due to the stone altar that was found there. The altar is surrounded with double axes stands.

The Caravan Serai.

It is located opossite to the Great Palace and it was the official entrance to the palace. It served as public baths with running water, where the traveller or visitor of Knossos should bath before visiting the King.

The Royal Temble Tomb-Sanctuary.

It is located south of the Palace and it is considered to have belonged to one of the Last Minoan Kings.

On Friday 23 March 1900 at 11 a.m. Arthur Evans began his excavation of Knossos. Although he was not the first to excavate at the site, that honour belongs to a Greek appropriately called Minos Kalokairinos in 1878, it was to be Evans who uncovered the Knossos Palace and brought to light a hitherto unknown civilisation — possibly the oldest in Europe. The basic excavation of the site took four years and for the rest of his life Evans continued working on the site, reconstructing and building, often in an attempt to preserve the remains from the weather to which they had been exposed for the first time in 3,500 years.

Evans designated the building at Knossos a palace and named the civilisation that had built it the Minoans, after King Minos of Greek mythology. Since then the actual function of the building and of the other palaces has been questioned and new interpretations advanced. Alternative views consider the four large palaces of Minoan Crete to be temples or administrative centres or both, and in one interpretation, Knossos is seen as a necropolis — a huge burial site to which only a small band of priests and embalmers had access. Here, following convention, the name Palace is used throughout.

Evans, like all of us, was a product of his time, and his time was Victorian England. He was an amateur archaeologist as were many archaeologists at the time. Only wealthy men of leisure could afford to carry out the kind of archaeological dig that Evans carried out at Knossos and professional archaeologists received even less government support then than they do now. We are fortunate that Evans was a rather better archaeologist than many of his generation, thanks in part to his father, himself an amateur archaeologist.

No less important, he had the support of an excellent team of British archaeologists including Theodore Fyfe and Duncan Mackenzie as well as talented Greeks including the Cypriot Gregorios Antoniou and the Cretan Emmanouel Akoumianakis, known as Manolaki, who much later was killed fighting the Germans in the Battle of Crete.

Mackenzie, in particular, was to play a crucial role in the excavations as he kept daybooks in which he recorded all the developments at the excavation site. He probably had the most scientific approach of any archaeologist working in the Aegean at that time. Sadly he later suffered from severe mental illness which rendered him incapable of working.

Although much criticism has been levelled at Evans in the intervening 100 years for the way in which he rebuilt parts of Knossos, matters might have been worse still if Heinrich Schliemann had succeeded in buying the site of Knossos. The story goes that if the Turk who was selling the land had not exaggerated the number of olive trees included in the sale and thereby incensed the businessman in Schliemann then he and not Evans would have been the owner of the site and Knossos might have been excavated in the same insensitive way that Schliemann excavated Troy.

Given Evans’ background in the wealthy middle class of Victorian England it is not surprising that he superimposed an image of British monarchical society onto Minoan society. Evans identified Knossos as a palace and then set about identifying the various rooms used by the Kings and Queens of the Minoans. He also rebuilt large parts of the site. In some cases this was clearly unavoidable. The great staircase, for example, would have collapsed onto the workmen on the site if action had not been taken to restore it.

It is perhaps a fruitless task to criticise from the position of today’s scientific approach to archaeology what Evans did then. We should be grateful that he was willing to sink so much of his personal fortune into the excavations at Knossos and devote the rest of his long life to the study of the Minoans. We don’t have to accept everything he said about that civilisation — a further 60 years of excavations have taken place since Evans’ death. But Evans provided the basis on which all further study of Minoan society has been based.